It seems like for the past year I have been treading the rural backwater, so to say that I’ve hit the furthest-flung reaches might sound redundant. But it’s not.

It seems like for the past year I have been treading the rural backwater, so to say that I’ve hit the furthest-flung reaches might sound redundant. But it’s not.I had heard about Ventisquero (the hanging glacier) Valley for some time. I tried to go twice but was foiled. First in September by a horse accident, and second in December by a travel partner unwilling to trod the eleven hours in on foot. A local claims that the valley is bewitched and “mañoso,” picky: not letting just anyone enter, and sometimes keeping travelers at bay for weeks with storms and swollen rivers. In short, it sounded to me like the kind of place where folktales and fairytales were still being manufactured.

This time I took my time and contracted a local guide, the only who would agree to hoof it (walking is second class, riding is first). Still, we traveled with a packhorse to carry provisions and cross rivers with. We set out on a blazing hot summer day, horseflies swarming us as we made our way up valley.

My final destination, reached a few days later, was the ranch of Don Leonidas, age 79. He was the last of the old school of cowboys, arrived as a child in the valley and was brought up making a home out of the wilderness. When he was 22 he rode to Argentina to get a wife, and while before he was suspected to be a bandit, these days he is a local patriarch, the guy they send to the grade school once a year to tell the kids about the old days.

When I asked if I could tape him he took one sidelong glance at my silver recorder and asked how could he be sure it wasn’t a pistol. Sometimes being five foot tall and minimal works to your advantage. I just shrugged.

All the while an orphan sheep cried in the background (if they are bottle nursed they resist weaning and follow their owner around like a lapdog) and Doña Licha told me about her own milk miracle. When her daughter abandoned her granddaughter at their house she was able to breastfeed her, up until the sturdy age of eight. Doña Licha must be Ventisquero’s patron saint of dairy, she also showed me a separate hut where she makes cheeses and offered me a chunk of the mild stuff (like munster”), wrapped in an old plastic food wrapper, to bring home.

A gracious host, she hasn’t been out of the valley in at least twenty years (unlike her husband, who rides to town once a week). She says she won’t either, because she can’t get on a horse because of a hernia. When asked if she’d have it operated on, she replied in her baritone voice, “For what? Just let it be, I should be dying soon enough anyhow.”

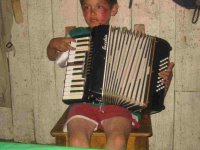

On my second day their great grandchild, known as Juanito Accordeon (little Juan accordion) emerged from the attic, painfully shy but bribed by his great-grandma to play a few songs for a candybar. His instrument is an antique that he’d picked up lying around the house, and the keys stick in the humidity, making his little brow furrow.

Juanito plays accordion and guitar, mostly Mexican rancheras, and is seven years old. Doña Licha danced and slapped her thighs. The accordion appeared to crush Juanito, his two spindly legs sticking out, but he played with gusto, with the rapidity of a field mouse darting hole to hole. Juanito is the kind of kid that doesn’t talk unless it’s through an instrument, and then does so beautifully.

I have plans to go return to the valley in March, to get more stories and more cheese.

No comments:

Post a Comment